We turn on a faucet to brush our teeth, water our gardens, and make a morning pot of coffee, but what happens to that water once it’s used?

In the Delaware River Watershed, this question isn’t just idle curiosity; it’s central to managing our most vital resource — water. The concept of consumptive water use describes the water withdrawn and does not return to the watershed, whether incorporated into manufactured products, evaporated, or exported outside the basin. Despite a growing population, water usage in the basin shows promising trends. Water consumption by public utilities is declining thanks to efficient practices, and industrial water use is also decreasing. Although nuclear power plants are the most significant water consumers in the Basin, their usage remains stable.

The most significant chunk (69 percent) of consumptive water use is out-of-basin diversions . These withdrawals are transported to provide clean and safe drinking water to New York City and northern New Jersey. Locally and within the watershed, the primary water consumers are power plants, public water suppliers, industrial facilities, and irrigation systems. The consumptive use of water varies significantly between these different sectors. For instance, agricultural irrigation consumes more than 90 percent of the water that’s actually drawn due to evaporation. On the other hand, public water utilities typically consume just 10 percent of the water they draw because most of the water used in homes and cities goes back into the system via sewers.

Keep utility-supplied water usage stable by:

+Planting native plants that don’t require water once established. Outdoor sprinklers account for 40 percent of household water use during the summer.

+Installing household appliances and fixtures that have the EPA’s WaterSense label. These fixtures are more efficient and could save you money.

+ Shortening your shower time by a minute or two. This practice saves up to 150 gallons per month (showers use less water than baths, too).

+Using rain barrels and similar water-saving methods at home.

What is Being Done?

The Delaware River Basin Commission continually tracks and assesses water use within the Delaware River Watershed to produce policy and help make informed decisions.

DRBC projects future water needs in the watershed

DRBC provides water conservation information

DRBC policy for consumptive use replacement for power generators.

Building Connections:

How does Consumptive Water Use assessment connect to the strategies and goals outlined in the Delaware Estuary Program’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP)?

CCMP STRATEGY W3.3: Promote water conservation and water efficiency by utilities and industrial water users

CCMP STRATEGY W3.4: Provide outreach and technical assistance to promote water conservation and infiltration by residential and commercial users and communities

This consumptive water use indicator status report is based on research compiled in the 2022 Technical Report for the Delaware Estuary and Basin (2022 TREB). Please refer to this document for more information.

What do bubbling streams and lush aquatic vegetation have in common?

They both contribute to an essential life-supporting element in our waters – dissolved oxygen (DO). Just as humans need oxygen to breathe, so do the countless creatures that inhabit our waters’ aquatic environments, from fish to invertebrates. Dissolved oxygen is essential for marine life, entering rivers and oceans from the atmosphere and through photosynthesis via aquatic vegetation. However, disrupting the balance of oxygen in the water can pose a risk to these ecosystems. Despite challenges, significant progress has been made since the 1960s, partly due to ongoing monitoring and control of harmful nutrient discharge (like excess carbon and nitrogen). Many areas historically low on dissolved oxygen now meet the necessary standards to support life. Fish such as shad and striped bass are rebounding, but there are still areas struggling with low oxygen levels during the summer, underscoring the need to continue working on the health of our waters. This section explores the factors that alter the amount of dissolved oxygen levels and how to improve them.

The health of these water systems hangs in a delicate balance, with oxygen levels depending on species and their life stages. Human activities, such as overuse and improper use of fertilizers and discharge of partially treated sewage, can disrupt this balance, leading to excess nutrients like organic materials and ammonia nitrogen in the water. While balanced levels of phosphorus and nitrogen are essential to water health, too many of these nutrients can tip the scales and be harmful. During rainfall, nutrient-laden runoff enters the water and can trigger an explosive growth of algae, called an algal bloom. When these algal blooms exhaust their nutrient supply, they die en masse. Their decomposition consumes a significant amount of oxygen in the water. This leads to a sharp drop in dissolved oxygen levels, creating a hostile environment where fish and other aquatic organisms struggle to breathe and may die.

The Delaware River Watershed has historically had low oxygen levels during warmer months, disrupting the harmony of life especially in urban portions of the tidal Delaware River (i.e., Philadelphia, – Camden, New Jersey, and – Wilmington, Delaware, areas) and displacing the species that once thrived here. Efforts are ongoing to improve oxygen levels and reintroduce sensitive species to our waters. Most zones now meet the necessary standards to support life, and fish species like shad and striped bass are returning. Yet, areas remain where oxygen levels fall short, highlighting a need for continued efforts.

The story of dissolved oxygen in the Delaware River Watershed is one of resilience, recovery, and ongoing restoration. There have been encouraging signs of progress, but the journey isn’t over and challenges remain. Work continues for monitoring waterways and pushing for pollution reduction efforts to maintain and improve water quality. The health of waterways doesn’t just affect the fish and other wildlife. It’s indicative of the planet’s health for future generations.

+Help prevent nutrient-rich runoff from entering our waterways by making changes on your property by:

+Reducing the use of fertilizers. Conduct a soil test and only apply correctly what your property needs

+Maintaining your septic system properly

+Intercepting rainfall and help water soak into the ground close to where it falls:

– Install rain barrels

– Plant a rain garden

– Install pervious pavement

What is being done?

The Delaware River Basin Commission is exploring whether dissolved oxygen criteria require revisions to protect fish reproduction.

The Philadelphia Water Department developed the Delaware Estuary Water Quality Improvement Partnership with other large regional municipal utilities to share strategic utility planning and technology evaluations in response to potential changes in water quality criteria that could impact acceptable levels of dissolved oxygen in local waterways and establish a foundation for communication and data sharing among municipal wastewater treatment facilities.

Long-term initiatives, like Philadelphia’s Green Cities Clean Waters program, aim to address potential threats to dissolved oxygen levels by reducing stormwater runoff inputs into combined sewer overflows (CSO). These antiquated systems have connected stormwater runoff and sewer lines. When flooding occurs, sewage mixes with the stormwater and overflows into our river. Initiatives like these help counteract human-generated stressors on our water bodies and work to improve water quality.

Building Connections:

How does monitoring dissolved oxygen levels connect to the strategies and goals outlined in the Delaware Estuary Program’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP)?

CCMP STRATEGY W1.5: Conduct research and monitoring on nutrient impacts in the Delaware Estuary for biological and ecological endpoints

This dissolved oxygen indicator status report is based on research compiled in the 2022 Technical Report for the Delaware Estuary and Basin (2022 TREB). Please refer to this document for more information.

What do waterproof boots, the popcorn bag you toss in the microwave, and personal care products have in common?

They all contain a variety of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs), which are continuously released into the environment as they are used. While they offer various benefits, such as waterproofing and providing non-stick surfaces, these chemicals also carry hidden costs, influencing human health and the environment in ways that are not yet understood. Two categories of recent CECs – per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) are of particular concern due to their persistence and accumulation in the environment. This section introduces the pressing issue of CECs by exploring the detrimental effects of these chemicals, their prevalence in the environment, and the scientific and regulatory efforts underway to mitigate their impact.

PFAS have earned the nickname “forever chemicals” due to their tenacious persistence in the environment. PFAS do not break down. They accumulate in water sources and even in our bodies. Certain levels of PFAS in our food and drinking water can negatively impact our health, including complications such as kidney disease, liver damage, and even cancer. PFAS have been discovered in drinking water and the fish we eat, with samples showing levels exceeding current safety recommendations.

Examples of PPCPs include medicines and everyday products like soaps and sunscreens. Like PFAS, chemicals found in these items resist breaking down and accumulate in our environment. Areas with high industrial activity, such as the tidal portion of the Delaware River, often show higher concentrations of these chemicals. While we are beginning to understand these products’ effects on human health, more research is needed to learn about their path into waterways and their lasting environmental impacts.

As these CECs gain attention, scientists are studying their impact and searching for ways to remove these chemicals to ensure the safety of our water and food sources. They are categorizing chemicals based on use or potential harm, developing new measurement techniques, and prompting sustainable practices like recycling and reuse to reduce the introduction of new ECs into our environment. Yet, keeping pace with the risks posed by the thousands of new chemicals created each year is challenging. This is especially true for contaminants in low concentrations and mixtures, which require very different monitoring tools.

Despite challenges, progress is noticeable. Enhanced detection methods, regulatory actions, and remediation efforts have increased our understanding to help address this emerging concern. Even as new contaminants emerge, ongoing research, monitoring, and cooperative efforts among state and federal agencies ensure we’re working towards a healthier and safer future for the Delaware River Watershed. However, patience is needed. Even after water quality improves, the effects of past pollution can linger. Tissue concentrations refer to the level of contaminants that have built up in the bodies of organisms. So even if the pollutants stopped today, it will take time for levels to decrease in an organism’s tissues. This fact underscores the need for continuous efforts to minimize pollution.

Current regulatory approaches may fall short in addressing these contaminants due to a lack of available information, and so public concern is rising over their environmental and human health implications. Therefore, future work should evaluate the source and potential effects of these contaminants in the Delaware River. This demands cooperation among national and regional partners and education to address the increased interest and concern about how these substances impact our water resources, environment, and health.

+Learn about chemicals in everyday products you use and shop safer and smarter by avoiding products that contain harmful chemicals.

+Encourage your officials to support regulations that minimize the impact of emerging contaminants on human health and the environment.

+Utilize household hazardous waste drop-offs to dispose of waste items/ household chemicals properly.

+Be sure to dispose of unused prescription drugs properly. DO NOT flush them in the toilet or rinse them down the drain! (Learn how to dispose of medication properly and find a pickup location for a drug take-back event near you here).

What’s Being Done:

The Delaware River Basin Commission periodically monitors for Contaminants of Emerging Concern in surface water, sediment and fish tissue. It works in cooperation with state agencies, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and academic partners on a prioritized list for further evaluation. The Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) began proactively testing for PFAS in 2019 to better understand the occurrence of CECs in the city’s water supply. Testing has found PFAS levels in the city’s water well below the criteria for drinking water in Pennsylvania to protect human health.Building Connections:

How does monitoring emerging contaminants connect to the strategies and goals outlined in the Delaware Estuary Program’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP)? CCMP STRATEGY W2.4: Coordinate and promote research and monitoring efforts (chemical, physical, biological) associated with the causes of water quality impacts throughout the Delaware Estuary. This emerging contaminants indicator status report is based on research compiled in the 2022 Technical Report for the Delaware Estuary and Basin (2022 TREB). Please refer to this document for more information.

Have you ever looked at the murkiness of our waters and wondered why it looks like that?

That cloudiness is often from sediment or mud )tiny particles of minerals and decaying organic matter) and holds immense significance for our plants, animals, and landscapes. It is the building material for the estuary’s marshes and shorelines and is where the life on the bottom of the bay and streams takes root. The balance of sediment in the estuary is a delicate dance: too little, and we risk losing essential marshland to rising tides, a concern that is increasingly pressing in our era of climate change; but too much, and we could potentially bury underwater habitats, blocking out light vital for bottom-dwelling plants and smothering developing fish eggs. This section looks at the crucial role of sedimentation, its challenges, and why managing this balance is more imperative now than ever.

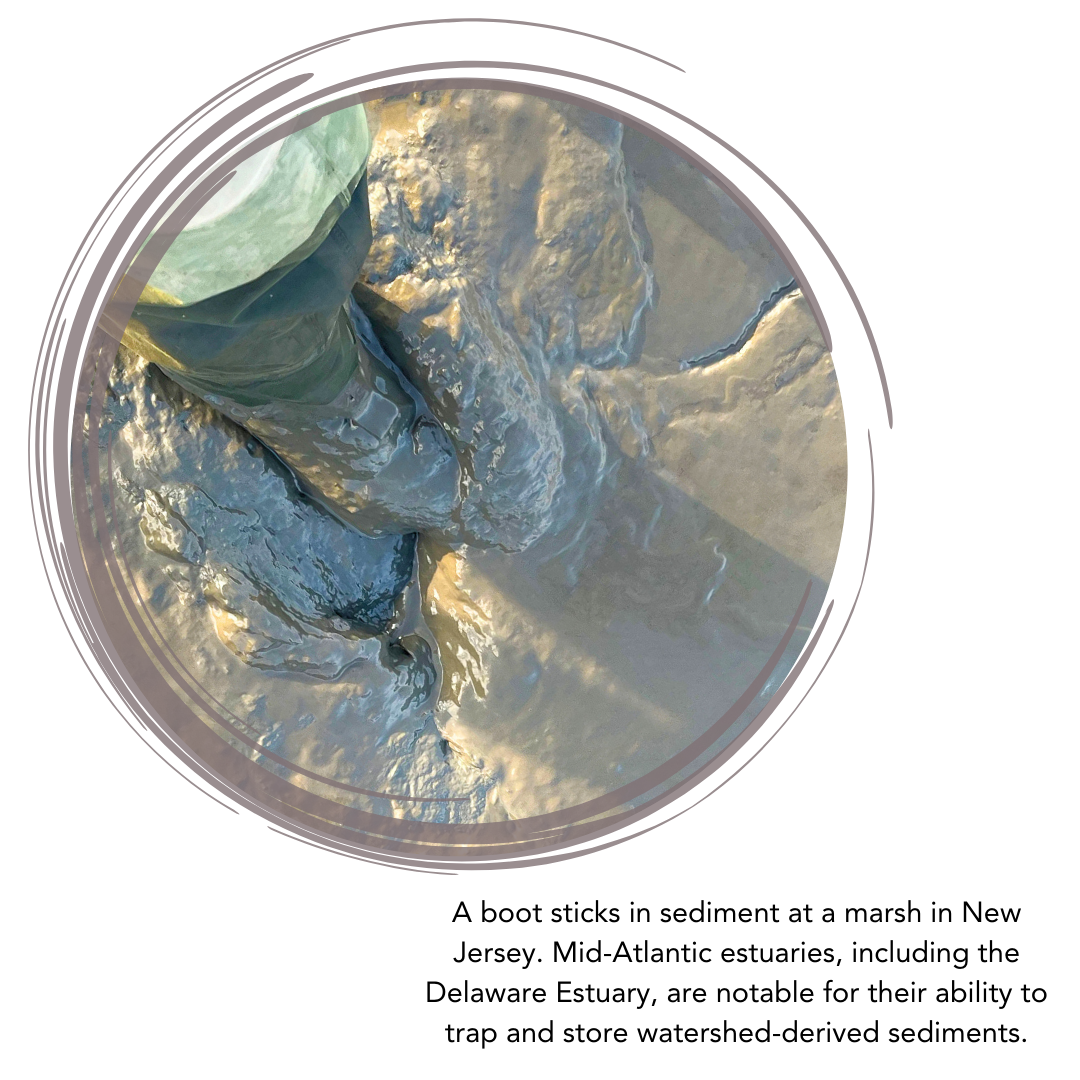

Mid-Atlantic estuaries, including the Delaware Estuary, are notable for their ability to trap and store watershed-derived sediments. Only 5 percent of these sediments wash out to sea while the rest stays where it should. This helps paint a picture of estuaries as sediment repositories, far more dynamic and impactful factors are at play that impact sediment processes.

One thing you can count on is that sediment is always moving. Sedimentation is the process in which materials such as decaying plants, animals, minerals, and debris are carried into the water and deposited or settled into a new location. This process is at the core of the Delaware Estuary’s vitality, shaping its landscapes and resilience against climate change. The Delaware Estuary receives a significant influx of sediment from its main rivers, with the Delaware, Schuylkill, and Christina rivers accounting for about 80 percent % of the freshwater flow into the estuary.

Sediments are crucial in maintaining our landscapes that are heavily influenced by water, such as marshes. Enough sediment must reach marshland to maintain its elevation above the rising tides. If sea level rise outpaces the amount of sediment that a marsh can accumulate, marsh’s sediment accretion, the marsh could drown and become risks drowning and converting to open water – resulting in lost an event that would result in lost coastal habitats and increased vulnerability of flooding and storm damage in coastal communities to flooding and storm damage. This scenario is particularly relevant in our era of climate change, with the tidal region of the watershed feeling the brunt of the impact.

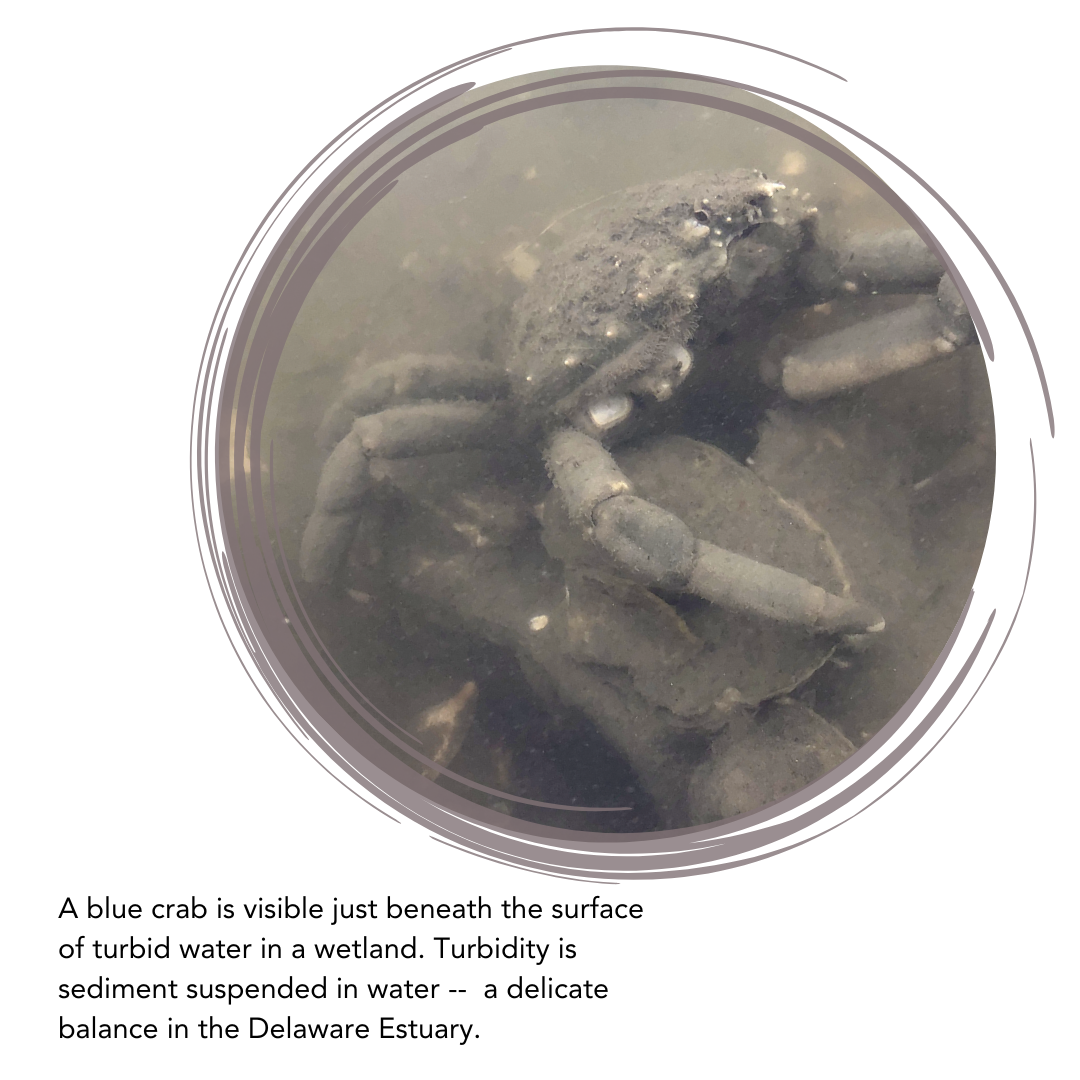

Turbidity is sediment suspended in the water – a delicate balance in the Delaware Estuary. When you look through highly turbid water, you cannot see fish, plant life, or the river bottom. Fewer suspended sediments in the water allow more light in, thus increasing the ability for algae or aquatic vegetation to grow, which is beneficial. Yet, this could also make the estuary more vulnerable to algal blooms, disturbing the balance.

Urban development can disrupt natural patterns of sediment flow. Similarly, climate change impacts, from more intense storms, or sea level rise, can affect sediment distribution. Even the good intentions of watershed management efforts, which aim to reduce sediment runoff to enhance water quality in upstream habitats, could inadvertently contribute to the declining sediment levels in the Delaware Estuary.

Further research and monitoring are necessary to clarify the reasons for this decline and its long-term implications. Understanding the effects of changes in land use on estuarine turbidity and long-term trends from historical satellite imagery could provide invaluable insights into managing our estuaries better.

+Support living shoreline projects that protect marshes from erosion and damaging waves. Volunteer to bag oyster shells, which are used in these projects.

+Brag about our major league mud! Every new major league baseball is rubbed down with mud from a secret spot on the Delaware River.